Today I sent my final manuscript for How to Be a Sinner to the Press. Several friends had read drafts, and most of their comments addressed the tone of my writing, rather than the content. So the Press engaged the best copy-editor I know: Patricia Fann Bouteneff. There were multiple lessons for me to draw, vis-à-vis …humility.

Today I sent my final manuscript for How to Be a Sinner to the Press. Several friends had read drafts, and most of their comments addressed the tone of my writing, rather than the content. So the Press engaged the best copy-editor I know: Patricia Fann Bouteneff. There were multiple lessons for me to draw, vis-à-vis …humility.

Some of the factors at play:

- She’s excellent at this work. She has decades of copy-editing experience. She’s worked on all my books and many of my essays. She knows me, and what is sought from her work.

- She is my wife. We are likely to talk about the book in the same time that we talk about emptying the dishwasher and who’s baking the bread.

- She is my wife. We talk about what’s wrong with my prose (and sometimes my ideas) in the same time that we talk about other problems.

- Did I mention already that she is my wife? Remember that a lot of what this book is about is humility and realism in dealing with one’s faults… That means that I am obliged—by the laws of the book and those of marriage—to, umm, be humble, as I watch my lovely prose get sent through an excellent but ruthless machine.

Generally speaking, being edited can challenge the ego. Writing, for me, is both very hard work and also a pleasure. When I’ve put in the hard work, I am liable to be pleased with my prose. The trick for me has been not to become attached to it.

This book took a couple of years to write, and all my drafts were written in prose that I thought was warm and accessible. I liked it! But as readers weighed in, it turns out that it came across as chatty with too much extra fluff. So Pat knew what she had to do. And I had to brace myself—partly because I know how she works. As a rule, prisoners are not taken.

Generally speaking, Pat is not one to stroke my ego. She’ll tell me when I’ve done something well, but won’t dwell on it. She also trusts me enough to be quite frank about my shortcomings. (Those, she can dwell on!) Seriously though, he helps ensure that I don’t develop an unduly large ego, and this is one of the many ways she plays a part in my salvation.

So the other week she sent me the edited manuscript, with changes tracked. I know from past experience that this can be exciting, but also painful. This time around, I decided to take my next editing pass without seeing the changes. This helped a great deal, because rather than see my precious prose go through the shredder I found myself simply reading a crisp and clear product that, for the most part, sounded like me. It sounded, in fact, like the me I’d like to be, stylistically speaking.

In places, I knew what had been taken out. Sometimes I was just as happy or happier without it. In other places I brought back some discarded material, but in an altered, crisper form. Every once in awhile, just out of curiosity, I would click on “view all markup” and would pale at the sheer quantity of excision. But then I’d take a deep breath and go back to reading the-me-I’d-like-to-be.

Generally speaking I did better, emotionally speaking, through this process than I had for some of my previous books. I attribute this to a couple of factors:

- For the most part I didn’t look at the “trash pile” of my excised prose.

- I’ve been through this enough times now that I’m more like, “whatever.”

- Pat and I have grown, and grown together, in our 25 years of marriage.

- And finally, I do mean it: this book’s themes simply don’t allow me to be a jerk about my writing. The book, after all, is about humility, faults and their correction, surrendering attachments, fostering compassion, and ultimately about peace of soul. So if I’m going to get behind my material, I’d sure better do it while I’m writing it.

Thank you, Patricia.

Etty Hillesum is someone to get to know better. A Dutch Jew during the Nazi period, she became increasingly interested in the Bible and in Russian literature (especially Dostoevsky). Over time, and notably during her time in concentration camps, she kept diaries that would justly earn her the reputation of being a genuine mystic. She knew the darkness within us, better than most. But was always more focused on the light, without losing her realism.

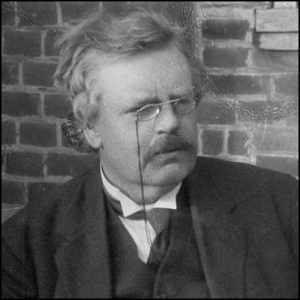

Etty Hillesum is someone to get to know better. A Dutch Jew during the Nazi period, she became increasingly interested in the Bible and in Russian literature (especially Dostoevsky). Over time, and notably during her time in concentration camps, she kept diaries that would justly earn her the reputation of being a genuine mystic. She knew the darkness within us, better than most. But was always more focused on the light, without losing her realism. The 20th-century writer G.K. Chesterton, when asked “What’s wrong with the world?”, had a pretty remarkable answer. He said, “I am.”

The 20th-century writer G.K. Chesterton, when asked “What’s wrong with the world?”, had a pretty remarkable answer. He said, “I am.”